How to Give Notes Without Being a Dick and Get Notes Without Getting Upset

This post may seem like it’s coming too soon. I’ve only just talked about the basics and now we’re talking about reviewing our work? What about all the steps in between?

We will get to those steps! I’m covering this topic now because I’ve opened up sketch submissions to paid subscribers. A few brave souls have already shared scripts with me, and I’ll soon begin sharing these with notes from me. Before that happens I wanted to say a bit about the process of giving, getting, and implementing notes.

(This is also a reminder that if you would like to submit sketches, see notes on submitted sketches, or comment on submitted sketches, this feature is only available to paid subscribers, safe(ish) from trolls behind the paywall.)

So, you’ve written a sketch. Now it’s time to share it with someone else. Ideally, multiple someones else. You might be looking at your script, feeling anxious about other people reading it. And these jerks aren’t just going to read it. They’re going to tell you what they think of it! Those assholes!

It’s normal to feel nervous about sharing your work, especially in the beginning. If you’ve written only one thing, the response to that script can feel like an indictment of your ability as a writer, or even your value as a person. It is not. You are simply getting feedback on a few pages. Don’t fear the notes; welcome them. They all have the potential to make your sketch better, even if you suspect your sketch is unsalvageable or already perfect. I’ve never seen a sketch so broken it couldn’t be saved, nor a sketch so good it couldn’t be improved.

I strongly suggest you find a group of other writers to critique your work. Your peers understand the small, invisible challenges of writing, and may have already found solutions to your problems while puzzling through their own. Working with the same group of writers also has the benefit of making the notes process easier, and eventually enjoyable. One person bombing is a drag, but nothing unites a group quite like shared embarrassment. Some of the moments I’ve laughed the hardest were in note sessions.

How to Give Notes (Without Being a Dick)

When you’re giving notes, you have two tasks: diagnose problems and communicate them clearly and courteously. Contrary to what some people might think, the second is just as important as the first. But don’t take it from me, take it from Emmy Award-winning writer Dan Gurewitch who texted me this after the launch of Chuffah:

If your doctor realizes you have a serious health problem it’s not at all helpful for them to deliver that news by saying, “Shit, dude, you’re fuckin’ dying!” Even if they were 100% correct, you would say that’s a shitty doctor. When you’re giving notes, you are a script doctor. You want to identify the right problems and communicate them in a way that’s actually helpful.

Diagnosing the Sketch

When you’re first reading a sketch you want to be hyperaware of your reactions. Read the sketch all the way through and look for the moments that elicit an emotional change in yourself. Positive and negative. Even if you don’t yet know why you felt what you did, make a mark on the page when it happens. These are the moments to examine more thoroughly after you finish the first reading. The parts that made you laugh will unlock the strengths of the sketch and the parts that made you feel bad will point to some kind of problem. After the reading, look through the sketch again and examine why these particular parts of the script affected you. Some specific things to look for:

Your First Laugh: This will likely be the first time the audience laughs too. After the reading consider whether this moment came soon enough, and consider if the comedy inherent in that moment is being replicated elsewhere in the sketch.

Your First Moment of Understanding: At what point in the script did you first say “Ah, I see what this is about.” When did you first understand the game? After the reading, see if the sketch continues this same game through the end, or if it changes at some point. If it changes, is one game more fun than the other? Which game should this sketch play?

Your First Surprise: When were you first caught off-guard by the sketch? Is this surprise satisfying (perhaps a great joke) or confusing (an off-game move)?

Your Favorite Moment: Some of your notes can and should be compliments! For one, the note session will be a lot more fun if you take time to talk about what’s good. Positive notes are also useful as writers head into second or third drafts. Old jokes don’t hit the same way after reading them dozens of times. Sometimes writers will take out exceptional jokes because they simply got bored of them. Don’t let that happen! Tell your jokes you love them before it’s too late!

The Onset of Boredom: When do you first start feeling bored? After the reading consider why. Has it been too long without a beat? Or are the beats not heightening? Is it too predictable? Something made your mind wander. If you don’t know what it is, the clues are here in this moment.

The Onset of Confusion: Did you ever get confused? This could be as small as an awkwardly worded line or as big as an unclear game move.

Joke Flops: Are there any lines clearly intended to be funny that you didn’t like? After the reading, consider why it didn’t work for you. Is it overdone? Poorly worded? Predictable? Unearned? What element of truth or surprise is lacking? How can it be rectified?

Delivering the Diagnosis

If you’re able to answer the questions above you might have some ideas about what’s working and what needs work. Now you need to communicate them to this nervous, vulnerable writer in front of you. Remember that getting notes is hard. It is the creative equivalent of standing naked in front of your friends and asking them to point out your flaws. If you’re giving notes you should be honest but gentle. Here are some tactics to consider:

Personal Phrasing: Choose words that center your notes around your personal reactions and feelings to reading it. There is a huge tonal difference between “This joke isn’t funny” and “This joke didn’t work for me.” The former suggests the joke itself is inherently, irrevocably bad. The latter implies that comedy is subjective, that the joke can be made to work, and that you, the noter, may ultimately be wrong. This is a better frame of mind for discussing the writer’s work, and how it might be improved. Speak to the emotions you felt in that first reading when you noticed something was off. The phrase “this bumped me” is very handy. The idea of “bumping” is connotatively neutral. It describes the feeling when something in the script stopped running smoothly, which is exactly what you’re looking for on that first reading.

Make Suggestions, Not Mandates: You have opinions. You think you have answers. You could be right. You could also be very, very wrong. And ultimately this is not your script. Don’t demand changes, or insist on your rightness; suggest possibilities. Instead of bullying the writer into your way of thinking, invite them to imagine alternate versions with you. Show them why your ideas are fun. I often use the phrase “I wonder if…” before offering an alternate path because, frankly, I don’t know if this other path is better, but I think it would be fun to wonder about together.

If You Point Out a Problem, Offer a Solution: This shows that you’re there to help build something together, not just tear down what the writer has already built.

Make a Shit Sandwich: The shit sandwich is a noting method where you pile all your negative notes between two positive notes. Start with something nice and end with something nice. The thing about receiving a shit sandwich is you definitely know when you’re eating one, but a shit sandwich still tastes better than a breadless pile of shit. Those positive notes really do a lot.

When in Doubt, Discuss: It may be that some part of the script isn’t working for you, but you can’t figure out why. Luckily, you don’t need to have the all the answers all the time. You’ve got at least one other person there, the writer, to help you sort it out. Sometimes it’s enough to say “this moment bumped me” but admit that you can’t figure out why. Sometimes you’ll find the answer just by talking more about it. A question is almost always helpful. If something confused you, ask what they meant. If you don’t understand the game or the POV, ask what the writer intended. Sometimes a very good idea gets overthought, and a writer has to be gently directed back to the thing that first made them laugh.

How to Get Notes (Without Getting Upset)

I hope you were polite when giving your notes, ‘cause guess what buddy? It’s your turn to get ‘em. Your job when receiving notes is to listen. That’s it. But you have to really listen. Here are the most important things to keep in mind:

Really, Really Listen: If this is a cold read there’s a lot you can learn from listening. How do people react the first time they hear your jokes? Is a sentence clear or did you type an unintentional tongue twister? Can people follow the emotion enough to deliver an appropriate line reading? You can always get more thoughts from people later, but you only get one chance to see the first impression. These reactions are so important to catch that I’d recommend not reading a part in your own sketch on the first read-through. Yes, even if you have a very funny voice for that one character that only you can do.

Shut the Hell Up for a Second: With any piece of writing you always pour a little bit of yourself into it. This is somehow true even if you’ve written something like “Fart Gorilla, the Gorilla Who Farts.” Criticism of your work can feel like criticism of you and it’s natural to react in all kinds of inappropriate ways. Some people get angry, some will try to argue with notes, some will deny that the note has any merit at all. I, personally, have a tendency toward explanation — an extremely stupid need to explain WHY I made the bad choice I did, even if I know I’m going to change it in the next draft. Ultimately none of this is helpful. Resist the urge to argue. Don’t get angry if someone points out a problem. Don’t forget they’re here to help. Shutting the hell up for a second, is also a great way to be sure you’re listening (see above).

Write Down Every Note: In the moment, you might not think a particular note is useful. You might even think it’s bad. Write it down anyway. This will help you shut the hell up (see #2) and listen (see #1). It’s also often the case that in the cold light of the morning those bad notes from yesterday take on new clarity and they’re suddenly the most brilliant thing you’ve ever seen. Good thing you wrote it down! And good thing you used a shorthand you’ll understand later, because you definitely don’t want to be scratching your head the next day looking at something like, “no less fat part” and trying to figure out what the hell it means.

Ask Questions: If someone says they want more beats, take a moment to brainstorm while you have an extra brain there to help you. If someone didn’t like a joke, find out why. If someone says it doesn’t heighten enough, see if they can help you think of a more heightened alternative. This is your chance to trick a bunch of other people into helping you write! Don’t squander that opportunity.

Be Gracious: Even if you hated every note and squirmed through the whole critique process, thank everyone who helped you. These people are volunteering their time and mental energy to make your work shine. They probably aren’t getting paid. They probably don’t have to do this. And if you don’t show your gratitude they may not help you again. Positive vibes will keep the whole notes session on track. Thank them now, and then later you can grumble about how no one understands the genius of “Fart Gorilla, the Gorilla Who Farts” in the privacy of your sad little writing cave.

Implementing the Notes

What do you do with all these notes? You may have good suggestions buried in a pile of contradictions, tangents, bad ideas, and non-sequiturs. Here are some tips to help you navigate your next draft:

Approach with an Open Mind: You’re close to your work. You’ve thought a lot about it. If someone suggests something different your immediate reaction is probably to reject the note. And, to be fair, sometimes you will get stupid notes that absolutely should be rejected. But don’t let this stop you from honestly considering everything. Lower the defenses. Explore the possibilities. Even if you end up rejecting the note, you will probably have a clear reason why it doesn’t work, which means you now understand your work better than you did before, which will only help you in the editing process.

Look for Consensus: If you show your work to a bunch of people and all of them have the same note, you should probably implement that note. Even if you don’t agree with it at first, consensus warrants extra consideration. It’s far more likely that you have a blind spot than that you’re a misunderstood genius.

Look for the Note Behind the Note: Imagine one person said “I didn’t like this joke because it came out of nowhere” and another says “I thought it was funny because…” and then goes on to describe an interpretation of the joke you didn’t intend at all. You might not be sure exactly how to address this at first, but you can start to see a consensus implied by both notes — this joke is confusing. This is a problem you can fix. Cut the joke. Reword it. Add clarity elsewhere. Remember that the people giving notes are trying to offer solutions. Sometimes their solution may be off, but their diagnosis is correct. Or their diagnosis is wrong, but they’re still reacting to a real problem. Understanding the motivation and emotion behind the notes can sometimes reveal the true problem, even if no one noting your work was able to identify it.

Start with the Small Notes: Implementing notes can be mentally and emotionally exhausting. You have a big list of flaws and you have to address them all. I’ve found it’s helpful to start with the smallest, simplest fixes. The typos. The line tweaks. The simple, funny additions. You’ll build enough momentum that the rest of the list feels less daunting.

Build a Boneyard: Sometimes you’ll have a perfect joke that nevertheless doesn’t belong in the sketch you’ve written. If you can’t bear to cut this joke, build a boneyard. This is a separate document where you cut and paste lines you’re not using. This provides a little bit of a safety net — if you decide you want to put the joke back in,1 you know exactly where to find it — but more importantly it makes it psychologically easier to pull it out of your script. You’re not killing your joke; you’re just sending it to live on a farm upstate, where it can run around happily living its best life!

Cut Mercilessly: When in doubt, cut. Shorter lines are funnier. Faster beats are funnier. It’s much better to write a sketch that leaves people wanting more, than to write a sketch that wears out its welcome.

The Dreaded Page One Rewrite: Sometimes you’ll get a note you agree with, but it blows up your whole script. These are usually problems with the game or POV, something so fundamental to the sketch that changing it requires a complete rewrite. This can be dispiriting, but as long as you’re excited by the new angle you should pursue it. Some of the best sketches I’ve seen are unrecognizable when compared to their first draft.

And then edit until you’re done…

The cool2 thing about editing is that you can do it forever. How do you know when you’re actually done? The vague, artsy, philosophical answer is “when it feels right.” When you think every line is as good as it’s going to be, when there are no extraneous words and every pause is exactly where it should be… then you stop changing things.

The practical answer is “two to three drafts.”

In my experience, after three drafts you see severely diminishing returns on your time. You’re still making changes, but ones that are so small that your time is probably better spent doing something else. This is great news if you’ve done a few revisions and you’re happy with your script. It means you’re done!

But what if you still think your sketch isn’t working?

Well, it could be that you’re too hard on yourself. Maybe you can only see the flaws now, but it’s actually a solid script. Or maybe your sketch is actually bad! The cool3 thing is that you won’t know for sure until you put it in front of an audience.

But, again, the beauty of sketch is that the stakes are low. Even if your sketch flops, you’ll probably learn from the experience.4 And you can apply what you learned to the next one. Imagine writing a 100-page screenplay. That’s twenty sketches’ worth of pages! Twenty opportunities to apply new lessons. If you write a sketch that bombs don’t despair over how you failed; think how much better the next nineteen will be.

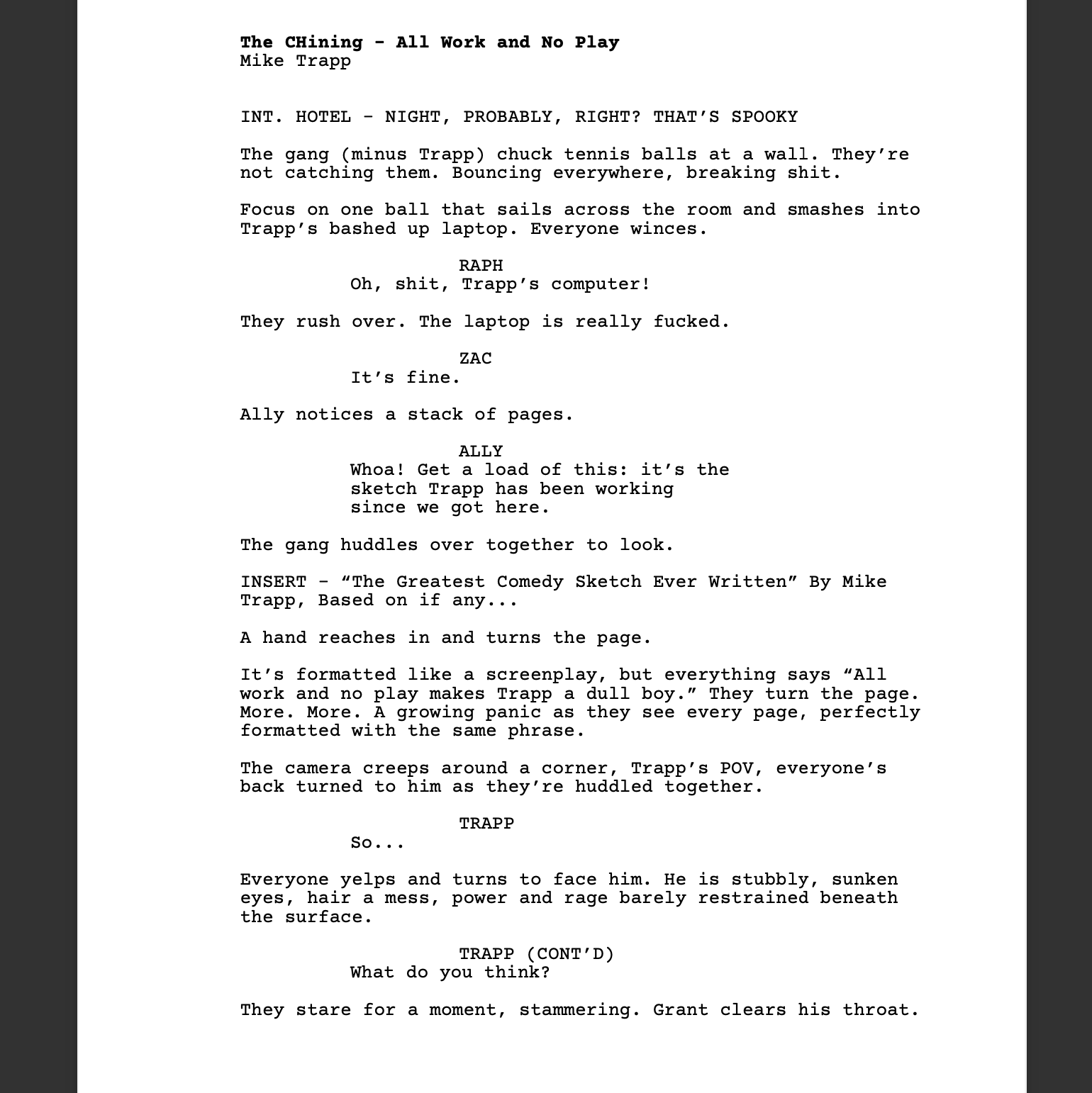

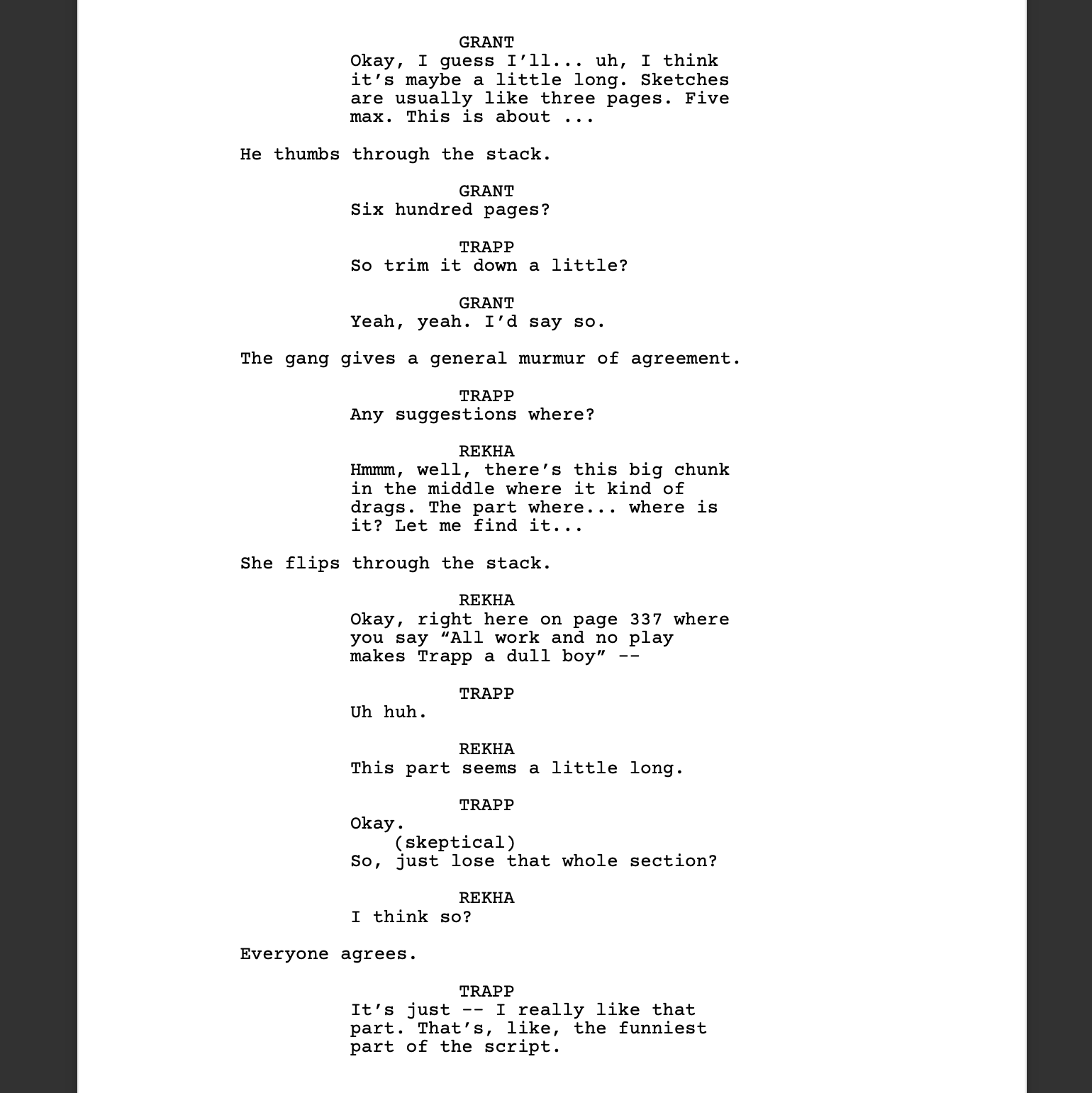

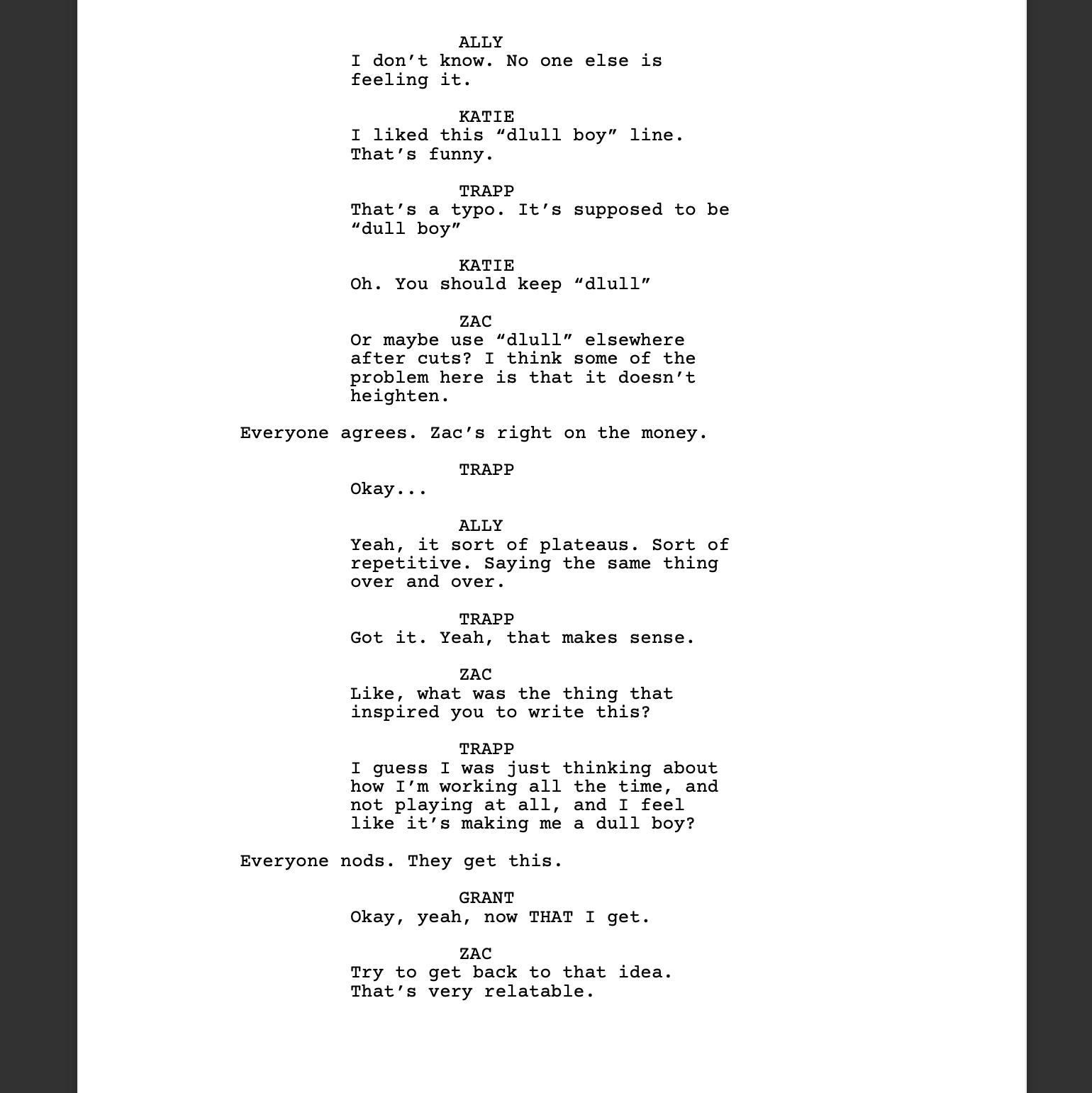

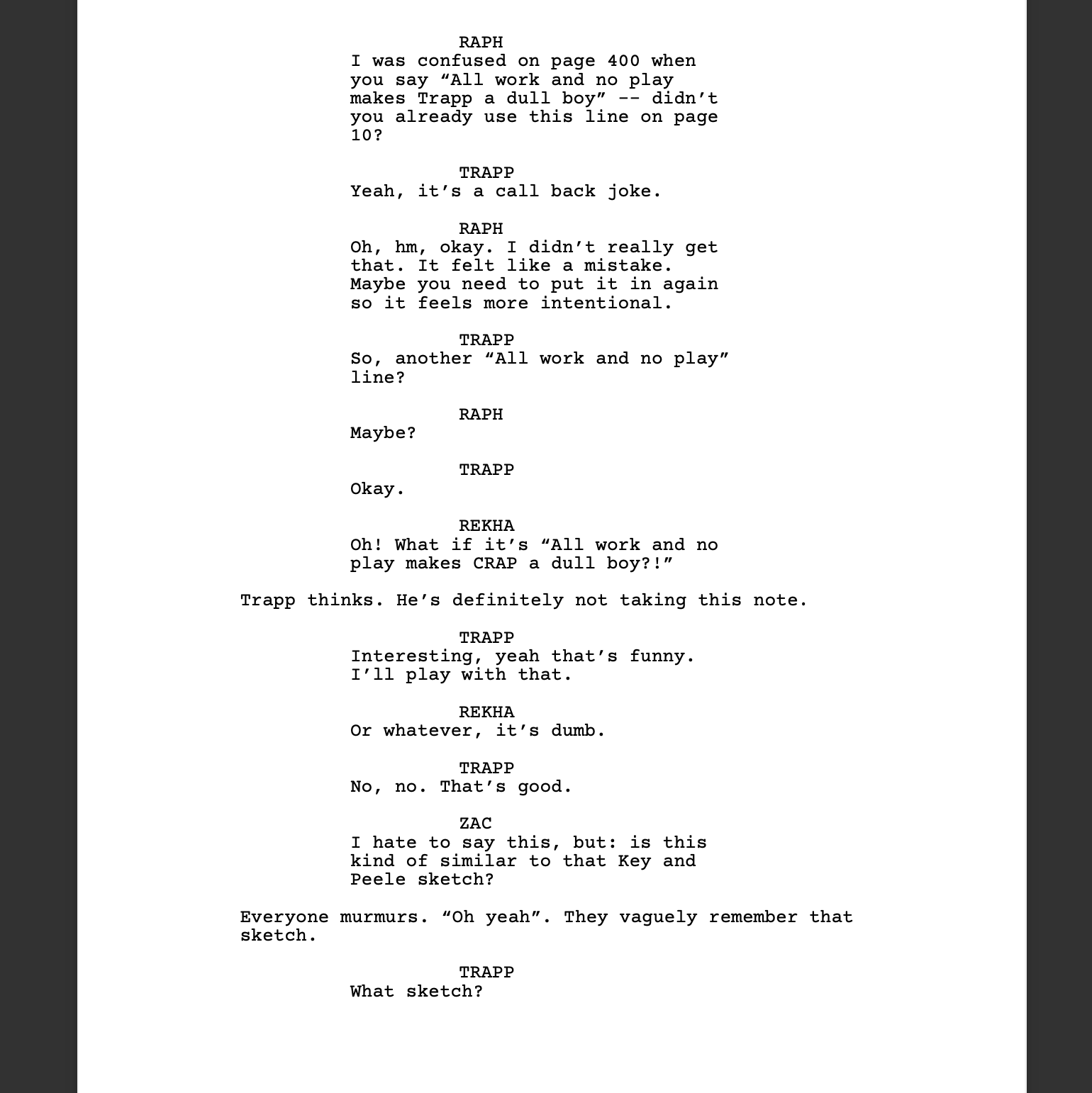

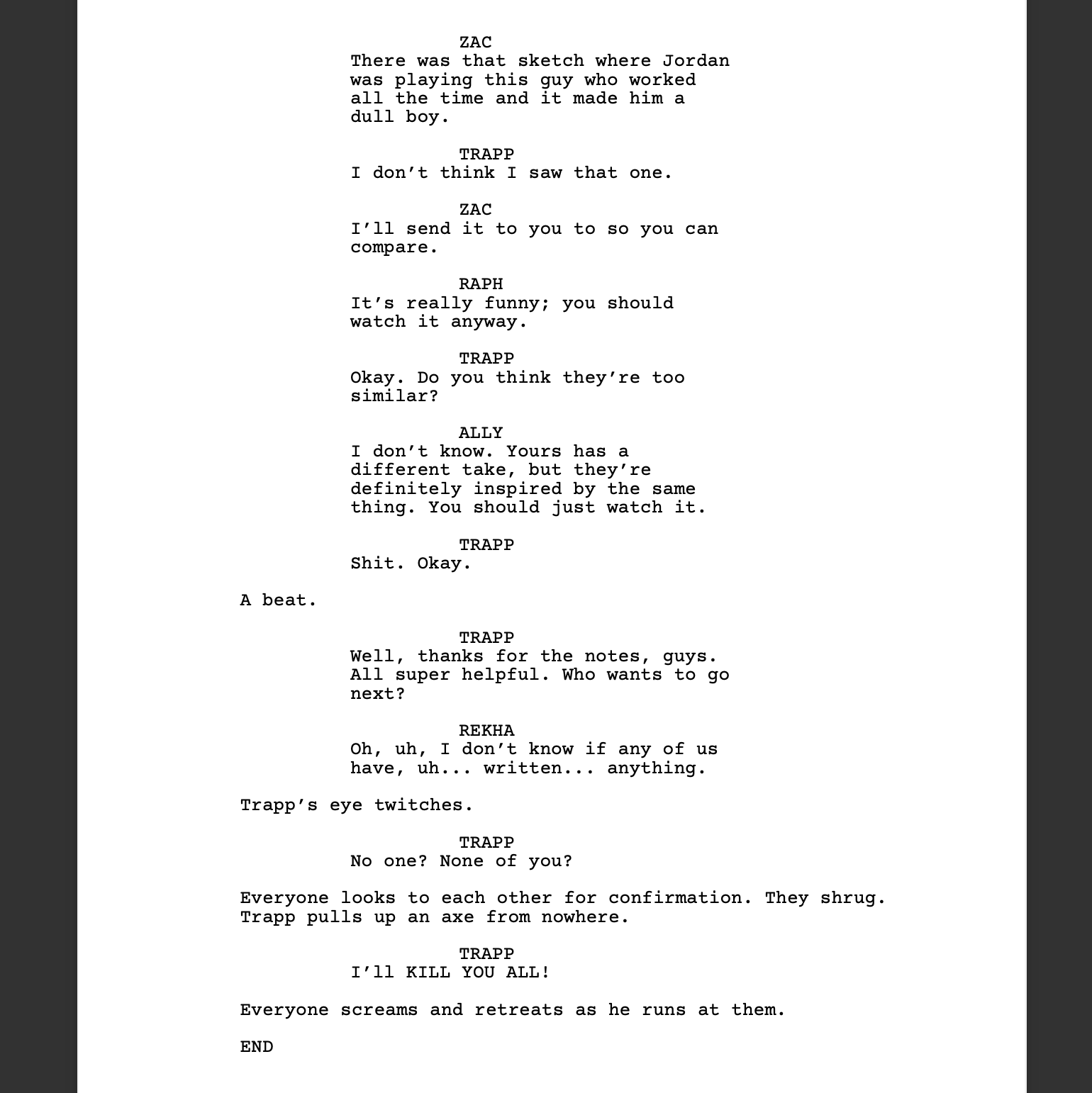

I’ll sign off here by practicing what I preach and sharing some of my own work. This is a sketch I wrote as part of a series of sketches parodying The Shining. This sketch is also about the notes process itself, so it seemed appropriate to this post. It imagines a world where a deranged Jack Torrance is still open to feedback on his insane manuscript. You can find both the original script and the finished video below.

I admit that I like this sketch a lot, and it already went through a few rounds of notes before being produced, but I wouldn’t be surprised if there were still things about it you would want to change. In a later post, I’ll share a very rough draft of a different sketch so you can practice noting something that’s less polished, but if you’d like an exercise now, you can try diagnosing this sketch. Look for those emotional shifts described above as you watch this sketch. If you found something you didn’t like, how would you communicate that to me in a way that is constructive?

And if you’re curious to see how this compares with the written page, here’s the original script:

I have a boneyard for everything I’ve ever written. I have almost never put an old line back in. It still makes me feel good to know it’s there.

“torturous”

“nightmarish”

Even if it’s, “I guess I should have taken that note.”

I especially appreciate the "start with the small notes"! Sometimes though, I know the whole thing needs a "page one rewrite", and the thought of "let me fix this typo JUST SO I CAN DELETE THIS WHOLE GODDAMN PIECE OF SHIT LATER" is so demoralizing that I run away and hide under my desk.

Something I've started doing recently is "metawriting." I saw a video about it, I can't find where now. You start off your writing work each day with a "metawriting" session: You open up a blank document and just write about your thoughts on your writing. I've found this helps a lot. It's a little bit like "morning pages" (Julia Cameron, "The Artist's Way") where you get your thoughts out for the day.

So my "metawriting" goes like this:

"My work is utter trash. I hate myself...I need more coffee...okay back with more coffee..I don't know how I'm going to fix that scene, no one understood it, no one understands me! No one understood Bob was trying to kill Jimmy.... Why didn't they get it...why??? Maybe because I didn't have any foreshadowing...should we try to have a scene with Bob where he..."

And then twenty minutes later, or an hour later, I'm getting into it again, I have some ideas, etc. and then I can start working on the piece. Sometimes it takes a long time and a whole lot of "this is trash and I hate myself and this is trash and I hate myself" but eventually it gets there.

Ooh seeing the comparison to the written page is super helpful