Hey everyone!

I hope you’ve been able to generate some sketch ideas over the past week. And if not, good news: you’ve got a bit more time! Next week I’ll talk a bit about outlines and brainstorming; this week I’m going to do a little sketch dissection. If you’re still struggling with generating ideas, I’ve got a thread open for paid subscribers to talk through possible angles.

It feels embarrassingly self-aggrandizing to start with a sketch that I wrote, but it’s also useful, since I can say with absolute certainty what the writer intended. It’s me; I’m writer. So I’m going to push aside my discomfort and break down Philosophical Truth or Dare.

Why this one specifically? This is one of the first sketches I wrote that I actually liked, so I’m a little sentimental about it. It’s also incredibly simple, which means it’s really easy to break down. I’ve seen it performed on stage a few times and I’ve adapted it to video, so I’ve seen it in different mediums and heard reactions from live audiences. And it’s evergreen, so you don’t need any context to understand what the sketch is about.

You’ll find the script below with numbers marking things worth talking about. I’d suggest reading the script all the way through first before looking at the specific notes. At the end of this post you’ll also find the video produced from this script.

The Script

Points of Interest

Sleepover Party!

The original opening of this was even weirder. It was “Sleepover Party? SLEEPOVER PARTY!” Either version might seem like odd ways to open a script, but I like them!

Screen directions can do so much more than provide basic descriptions. You’re not writing a recipe, you’re trying to establish a mood, conjure up images, and keep a reader entertained. You’re allowed to make your screen directions fun. I could have painstakingly described the kinds of things you would find at a sleepover party, but that would have been boring and a waste of valuable page space. The words “Sleepover party!” with an exclamation mark carries the tone of a squealing, excitable kid. It immediately establishes the tone of the rest of the piece. It’s shorter than the much drier alternative “We’re at a sleepover party.” And it’s more fun. Why wouldn’t you do something like this?Three girls in pajamas are sit in a tight circle…

Whoops, there’s a typo here: “are sit.” This is me owning my mistake and pointing out that even your screen directions should be typo-free (even if people will only ever see them if you start a newsletter years later and share your scripts). This is also evidence of an important change I was trying to make, so it’s worth pointing out: “Three girls sit…” is shorter and more direct than the original “Three girls are sitting.” The simple present tense is better than the present progressive.All right, Melissa, truth or dare?

Look how quickly you can start a sketch. No chuffah needed. You could have the characters engaging in some unrelated sleepover chatter, but you really don’t need it. This is a sketch about truth or dare, so let’s play truth or dare! You don’t need to ease the audience in; they’ll catch up fast. This is a good area to look at when you’re editing. Do you get to your game within the first three lines? If not, you may need some cuts right at the top.…this is gonna be a big one. I’m talking about a REAL truth here.

This is the line that establishes the unexpected connection that makes this sketch work. A “big” “real” truth within the context of “truth or dare” means something that is secretive and deeply embarrassing, but a big, real truth could also refer to a high-minded philosophical examination of the world. This is the surprising juxtaposition of the sketch. You have a contrast of opposites: high-brow philosophy with low-brow kids’ games. Important reflections on existence contrasted with frivolous gossip. These opposites are connected by the fact that we use the word “truth” to refer to both. We only need to establish this connection once, and that gives us the freedom to be as silly as we want for the rest of the sketch.Melissa covers her face with her hands.Why is this screen direction here? Is it necessary? If you have an active imagination, you might already be picturing what the other characters are doing. And you might wonder why this specific detail is important to highlight when I’ve already omitted so many others.

This line paints a nice little picture and it gives the actors something to do, but this line is primarily here for one specific reason:

Timing.

Notice how line breaks build a natural pause in your head while you’re reading? Jeanette’s next line is the the first big move, the one that establishes the game, and gets the first real laugh. I wanted to make sure this line got the weight of a punchline, and didn’t get crammed together at the end of her previous line. This bit of screen direction is mostly here to build a natural pause into Jeanette’s line and ratchet up the tension.

You may wonder why this sort of formatting matters if most people won’t be looking at the script. Because some people will. Important people. The actors will. As will the producers who decide whether to make your sketch at all. These people need to see where the jokes are, so don’t hide them. The rhythm of the page should enhance the rhythm of the comedy, not compete with it.Are humans inherently good?The first game move. This is usually the first laugh. It’s a surprise (you don’t expect these giggly tweens to start talking philosophy) but it’s also logical (she said she was going to ask about a big truth. That’s exactly what she’s done.)I can’t believe you asked me that!When this sketch is performed live, this line also usually gets a laugh. Why? Because it resets reality in a surprising way. Audiences will always assume that the sketch they’re watching takes place in our everyday reality, until they have evidence to suggest otherwise. This sketch seems to open with normal people in a normal world. So far, so good. Then Jeanette makes a weird statement about the inherent morality of humankind. Most people will then assume that Jeanette is unusual, but the rest of the world is still like ours. The response from Melissa is a surprising turn that makes the audience reevaluate the scene. It’s not that Jeanette is weird, the whole world of the sketch is.

It’s worth noting that you could write this sketch with one weird character instead. You could have the same game, with the same observation about the word “truth” but instead, only Jeanette is unusual and the other characters play straight man to her weirdness. This could work just fine! I decided to go the way I did because it felt more playful (all the characters get to play the game) and more energetic. But it’s not the right choice, just a different choice.Bottom of page 1

We now have a moment to explore before we get to our second beat. This moment of exploring continues to build off the reality of the scene and play up the core contrast. These characters still act like giggly tweens: they scream and cajole, and are scandalized by each others’ responses. And they still pepper their dialogue with “likes” and “I dunnos” but the content of their dialogue is all philosophical. We know the comedy in this sketch comes from that juxtaposition of contrasts, so we hit both halves of the juxtaposition and crank the contrast as hard as we can. Make them as smart as they can be but also as shallow as they can be. Make them swing wildly between the two. Make them somehow both smart and shallow at the same time.That’s not what Gina Meyer told me.This sketch has a very simple structure because truth or dare itself has a simple structure. Everyone’s going to take their turn. Everyone’s going to get a chance to play (both the game, and he game of the sketch). The second beat will come when the next person takes their turn. But we can’t repeat the exact circumstances of the first beat or it will become repetitive and people will stop laughing. So how do we shift things up?

In this sketch, I looked back to the reality of truth or dare. In real life do people always just say their truth and move on? No. People might try to lie, or weasel their way out of a turn, or try to end the game if it’s getting too intense. These moments feel real, and also let us disrupt the pattern just enough to keep the audience on their toes.

This particular line also explores the world of the sketch and once again reframes reality. It’s not just these girls just this one night gossiping about philosophical concepts. They have unseen peers who also do this, and they seem to be doing this all the time. These girls just gotta get to the truth.1Mom enters.This whole mom beat wasn’t in the original stage version of the sketch. It was only after I wanted to shoot it for CollegeHumor that it was added, based on notes from another writer.2 I think it’s a nice moment that breaks up the pattern, especially since there’s only one player left. The audience expects her to take her turn, so let’s throw a curveball at ‘em.

This beat is a good example of “if/then” thinking, a shortening of “If this is true, then what else must be true?” If young girls treat philosophical truths like gossip, what else does that imply? It could imply this mom beat… as well as a million other things that didn’t make it into the script.DARE!These characters are playing truth or dare. One of them must pick dare at some point. They just have to. But when I was writing the script it wasn’t totally clear the best way to have a dare that supported the game. Doesn’t this sketch rely on an observation about truth?

This beat is what I came up with — a dare that’s still about truth and philosophy. If I’m being honest, it still feels like a bit of a cheat to me, but it mostly works. Luckily, after a few beats you earn enough audience goodwill to get a little fast and loose sometimes.…reconcile the problem of theodicy!A few weeks ago, one of you asked a question3 about how to make inaccessible concepts comedically accessible, citing the “Treaty of Westphalia” sketch from A Bit of Fry and Laurie as an example. To restate the answer I gave earlier, if your game is comedically accessible, your specifics can be inaccessible. I don’t know how many people watching this sketch are familiar with the word “theodicy,” but, shockingly, it doesn’t really matter! They already know that these ditzy characters are going to say smart, philosophical stuff. To heighten, these teens should be speaking more and more intelligently as the sketch goes on, which means they should get so philosophical that even the audience might not totally understand what they’re talking about. But the audience will still laugh because they can tell it sounds smart. That’s enough for the comedic juxtaposition to work. And if they do know what theodicy means, then the joke still works. You win either way.4God is dead!And here’s the end. In live performances, at this point, the actresses are jumping up and down, clutching their pillows, and repeatedly screaming “God is dead” as the lights dim. That action isn’t explicitly specified in the script, but maybe you were able to pick up on that energy anyway. If I were writing it today, I’d probably be a little more precise in the screen directions, but I do think the “vibe” comes through the page.

This type of ending is a “blow.” A blow is an extremely heightened game move that ends the sketch with a lot of energy and a big laugh. Usually it’s a move that’s so heightened that the sketch has nowhere else to go. This ending isn’t quite that extreme, but it’s still big. Both halves of the juxtaposition are pretty extreme: the girls are jumping up and down, screaming in unison, but they’re screaming about the absence of God. Big places for both the “gossipy teen” part and the “philosophy” part. Do you need to know that this is a reference to Nietzsche to laugh at it? No. But if you do, it’s just a little extra joke that supports the overall game.

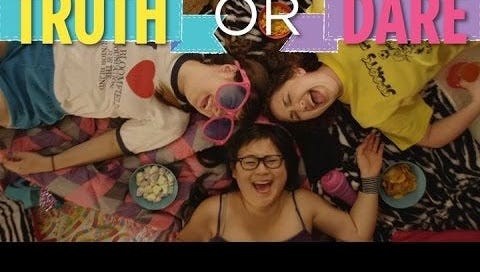

The Video

Exercises

What other beats might I have included in this sketch? Ask yourself, what else happens at sleepovers? How might you incorporate those in a way that supports the game of the sketch?

What other ways could the “Dare” beat be played? How might someone perform a dare that still supports the game?

What other ways might you end the sketch? Is there a more heightened beat? A surprising reversal? A killer one-liner?

How might you write the version of this sketch with only one unusual character? How would you heighten and explore in a version where only Jeanette drew the connection between truth or dare truths and philosophical truths?

A quick aside: if I were writing this sketch today, I would probably try to sneak one more philosophical language specific somewhere around “I’m gonna kill Gina when I see her again,” to keep hitting the other half of the juxtaposition. It’s not wrong as is, but that line feels like it could have a laugh in it that’s missing right now.

Pat Cassels

$hameless Ca$h Grab: If you want to comment, ask questions, see what other people are asking, and submit your sketches for notes, consider gettin’ that ol’ paid subscription for less than a buck a week.

Just a few lines later when Jeanette gets on the phone she provides the definition of the problem of theodicy contextually: “have you ever noticed that god is all knowing and all loving and yet evil still exists?” This gives the audience the definition, but does so in a way that presumes the audience already knew what the definition is. This is a great way to catch everyone up without being condescending to anyone.

I really love this sketch and the breakdown you've provided is very helpful. Here's my attempt at the exercises:

1. Possible beat/alternative to mom entering:

-Little brother (let’s say Jacob) enters the room and hears what they're doing. Stacy panics.

STACY: Jacob! Get out!

JACOB: Are you talking about the nature of reality and its many mysteries again? I’m telling!!

STACY: Jacob stop…stop…here…

-Stacy pulls a philosophy book out of her bookshelf. Jacob’s eyes look like they are about to bug out of their head as they look at the book.

JACOB: What…is…this?

STACY: It’s Lacan.

Jacob starts thumbing through the pages.

STACY: Read it in your room!

Jacob runs out.

STACY: God-little brothers are so annoying.

2. Possible different dare/ending. This might be stupid but what if Jeanette is dared to run down the street naked. Jeanette giggles and pulls at a sleeve but is stopped by Stacy. “No- emotionally naked. Run down the street and bare your soul!” Jeanette giggles and protests and Stacy pushes until finally Jeanette snaps and says something along the lines of

JEANETTE: NO…Stacy…you’re so bossy all the time. I’m not doing it.

STACY: Okay…geeze…I thought we were all joking. You don’t have to if you’re too much of a coward.

The girls share a meaningful look. This is likely a common and effective tactic that Stacy uses on people. Jeanette sighs heavily.

Cut to Jeanette running down the street

JEANETTE: I’m not sure if I exist!!!!

3. Only one weird one angle (I much prefer the way you’ve done it)- What if it’s a slumber party thrown by a nerdy girl who has a philosophy themed birthday? It’s all educational games and there’s philosopher Tiger beat style magazines and stuff. It gets more and more boring until one of the girls puts her foot down and says she’s not having any fun. The nerdy girl then goes..”Oh! You want to have fun?” and goes on some kind of hedonism or optimistic nihilism rant. The slumber party turns into a wild time as they all scream god is dead.

I didn't think of this when reading through the sketch, but while watching it the part with the mom made me think that the structure is sort of similar to a "typical pop rock song structure" where you have a first verse, second verse, then a bridge, before a last verse. You could argue that the typical "slumber party girl" responses to the question answers might be the "chorus". I dunno that there's anything to be gleaned from that sort of sketch-to-song structure comparison, but I thought it was interesting.

Regarding other slumber party things or other beats to go out on, there's always the scheming brother stereotype who has some unwritten duty to pull a prank on the sleepover (or maybe a younger sister who's "too young for the cool kids" and resents not being able to play along). It'd require some foreshadowing to make it clear that that's what they're doing, but interrupting the party with a typical badly-executed-prank style (jumping out of the closet to say "Boo!" for a cheap scare or something) that results in something else philosophical (a philosophical counter-argument for something, or possibly a non-sequitur that just loudly announces the claim of another school of philosophy (or even art movement like Dadaism)) could lead to a simple "Shut up, Bryce, get out of my room!" moment.