In my last open post about sketch packets, I passingly mentioned that some packets will request pitches for either segments or sketches, totally forgetting that if you’re writing sketches for yourself or a small group you rarely, if ever, need to pitch sketches. The whole idea of pitching a sketch might be a little foreign. After getting a pair of questions about it, I figured I’d devote a post to the topic.

What’s the Point of a Sketch Pitch?

Writers’ rooms use pitches all the time. Given how short sketches are, you might be wondering why. Let’s say it takes a minute or two to pitch a sketch… couldn’t a person read most of an actual script in that time? Yes. But the pitch isn’t really to make things easier for the listener, it’s to make sure you, the writer, are using your time most effectively.

Pitches are a way to guarantee your idea is worth writing before you start writing it, and therefore only a necessary part of the process if other people are able to define what’s “worth writing.” This could be because you’re part of a writing group that’s trying to maintain a consistent voice, or it could be because someone else is paying you to write. The latter is an especially good situation to be in, so it is handy to figure out how to pitch effectively, even if it’s not at all important when you’re writing for yourself.

What does a pitch sound like?

At CollegeHumor we would have a pitch session every Monday. We’d go around in turn, sharing our three-to-five ideas for the week before the head writer would choose the two ideas each person would tackle by Thursday.

A good pitch, to me, has the following information, not necessarily in this order…

The Title: What is the sketch called? In a perfect world, you’ll get a laugh out of the title itself. The title might also be a description of the game. Makes sense, right? If you’re putting a sketch online the only information the audience has is the title and the thumbnail. A strong sketch has a strong title. And the first audience for your title is the room you’re pitching to. This is your hook; people should want to hear more when they’ve heard your title.

The Inspiration: What made you think of this idea? In a good pitch, this will likely communicate a relatable, human element. In a weaker pitch, this will often suggest alternative angles.

The Game: Sometimes you’ve already covered it in your title, but if you haven’t, explicitly state what your game is. What’s the repeated pattern? What’s the interesting contrast? Where is the comedy coming from?

A Beat, or Two: Give one example of the game in action. Maybe two if you’re quick about it. Don’t give us every possible beat of the sketch, just one or two to whet our appetites.

Each of these should be a sentence or two. And together they basically say, “I have an intriguing idea (the title) that a lot of people will relate to (the inspiration). I know where the comedy is coming from (the game) and it would sound a little something like this (a beat).”

Pitches are oral and ephemeral. They’re not usually saved, and I have no old examples to show you. But I can give you a rough idea of what a pitch might have sounded like for an old sketch of mine.

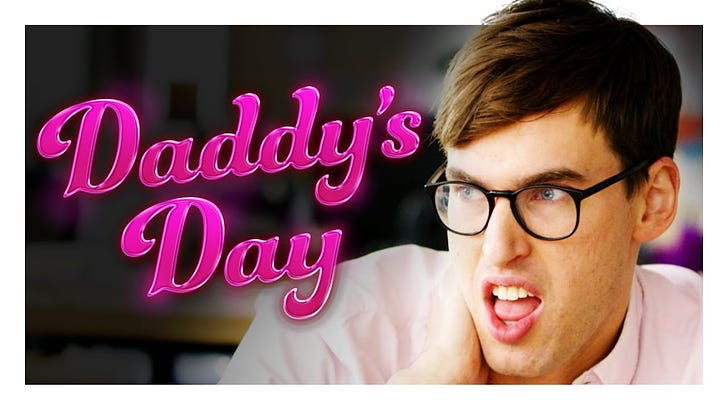

“Father’s Day is coming up so I want to write a sketch called Daddies’ Day. It would be people talking about typical feelings around Father’s Day but instead of talking about dads their talking about daddies…y’know, with a sexual connotation. It’s gonna combine the dirty talk you associate with “daddies” and the completely asexual way you’d talk about “fathers.” Like, people complaining that they don’t know what to get their daddies for Daddies’ Day because ‘ooooh what does daddy like?”

A pitch like this communicates why the sketch is worth making (it speaks about human relationships, it’s topical, it’s got an enticing, sexually suggestive topic). It also communicates where the comedy is coming from (the connected contrasts of “fathers” and “daddies.”) And, in case you still don’t get it, or want the comedy proven to you, there’s an example of what a beat might be.

What happens after a pitch is delivered?

The best thing that can happen after a pitch is discussion. That shows that you’ve hit on something people want to talk about. In an excellent pitch, people will immediately understand the game and start pitching beats.

In a good pitch, people might offer constructive criticism. The most common issue is that the inspiration speaks to something relatable, but the game needs some tweaking. Higher stakes. Broader vision. More exaggeration. As a group we’d try to do what we would usually do individually: identify what exactly is funny in that initial idea, and then exaggerate it to absurdity. Some of my favorite beats and turns of phrase in Daddy’s Day came from other people’s suggestions in the room, like the idea of a “deadbeat daddy” or the word “slam pig.”

You can tell a pitch bombed if no one wants to talk about it. The likeliest reason is in the inspiration — are you talking about something that feels too insignificant to engender an emotion in others? Or maybe your take feels untrue, and you need to do more convincing. If a pitch bombs, the best thing to do in the moment is laugh it off and move on to the next one (that’s why you bring a couple). If it’s an idea you still believe in, dig deeper and see if you can make the idea clearer.

What does a pitch NOT sound like?

A pitch is not a recitation of sketch structure. Don’t describe the setting or the characters, and definitely don’t provide a list of beats. The best way you can make people excited for a sketch is spurring them to imagine beats for themselves, to play the game in their own mind. Providing a list of beats robs them of this opportunity, and, even worse, will always make your sketch sound boring.

Think of it like a dish on a menu: you want an appealing title, and just enough description to make people start imagining on their own. Don’t give them the full recipe. Don’t even give them all the ingredients.

What does a pitch look like?

Pitches are usually verbal, which is great because you can really deliver it. You can control the timing of a joke, read a room, even put on a voice. (You can bet I’d say “daddy” and “father” differently in my pitch.) But sometimes you need to write down your pitches, either for packets, or because you can’t make a pitch meeting. I don’t think everyone will agree with what I’m about to say, but this is my newsletter, so fuck it: make it casual. If I’m reading pitches I want it to read the same way you’d say it. Write it the way you’d write dialogue. Sometimes writing a pitch can force you into overly formal language, which can make the idea sound drier than it is. Shake that out, and write like you talk.

And just for good measure

Here’s the video and script for Daddy’s Day — in case you want to see what the pitch turned into.

This is great!! Thank you for the example and for reminding me of this sketch haha

Thanks for this! It clarifies things, especially about how formal/informal these things should be (and how there's some disagreement on that).

(And also for sharing the script, this sketch always got a laugh outta me)